While it’s true that you are not your job, you do have a workforce identity when you’re part of the workforce.

It’s something you will probably discuss at some level with your manager during an annual review, with recruiters and hiring managers during job interviews, and with peers when you’re networking. You’ll probably also discuss it from time to time with a life partner, friends, or family.

This workforce identity I’m talking about is something that isn’t necessarily etched in stone. It can change, and though you can certainly allow others to choose it for you, you do have the power to ultimately choose and define it for yourself. If you want to tap into that power, it helps to get a grasp on some of the fundamentals involved.

2 Primary Career Paths

We’ll start by taking a brief look at the two most common career paths taken by employees in the workforce because these career paths are inexorably linked to the career roles and levels within organizations that we’ll cover later.

The Career Ladder

The typical or traditional career path is the career ladder. It usually goes like this… You start at the bottom and work your way to the top, moving from individual contributor into mid-level management and perhaps eventually into executive leadership.

For several decades, this was the predictable (and therefore was believed to be the most secure) path to take. However, you’ve probably noticed that as most organizations have had to become more agile in response to rapidly changing market conditions, they’ve become less likely to provide long-term employment to workers who want to nurture a long-term career ladder path within one organization. If you’re on a career ladder path, then it’s highly probable that you’ve been managing your career climb across several employers. The career ladder is certainly still a very viable career path for today’s workforce. You simply need to be savvier than previous generations had to be as you navigate changes along the way.

The Career Lattice

A more amorphous seeming career path is the career lattice. But even though this may look like an illogical path to others at first glance, it isn’t because there’s usually a plan. What drives your plan is solely defined by you, and your plan involves making lateral career moves and/or moves that are slightly upward or downward. These moves could be into different areas to gain well-rounded experience, or because you want to learn a variety of things out of plain curiosity, or perhaps in preparation for a later upward or outward move.

On the other hand, many take the career lattice approach because a management role simply isn’t calling them. There’s no desire to move upward. If your path looks like a career lattice for this reason, then you probably find it liberating to ignore the external pressures to take the traditional route. You may have come to realize that you can build a pretty rewarding career as an individual contributor if that’s what you prefer. It has its challenges, of course, but you know it can be done.

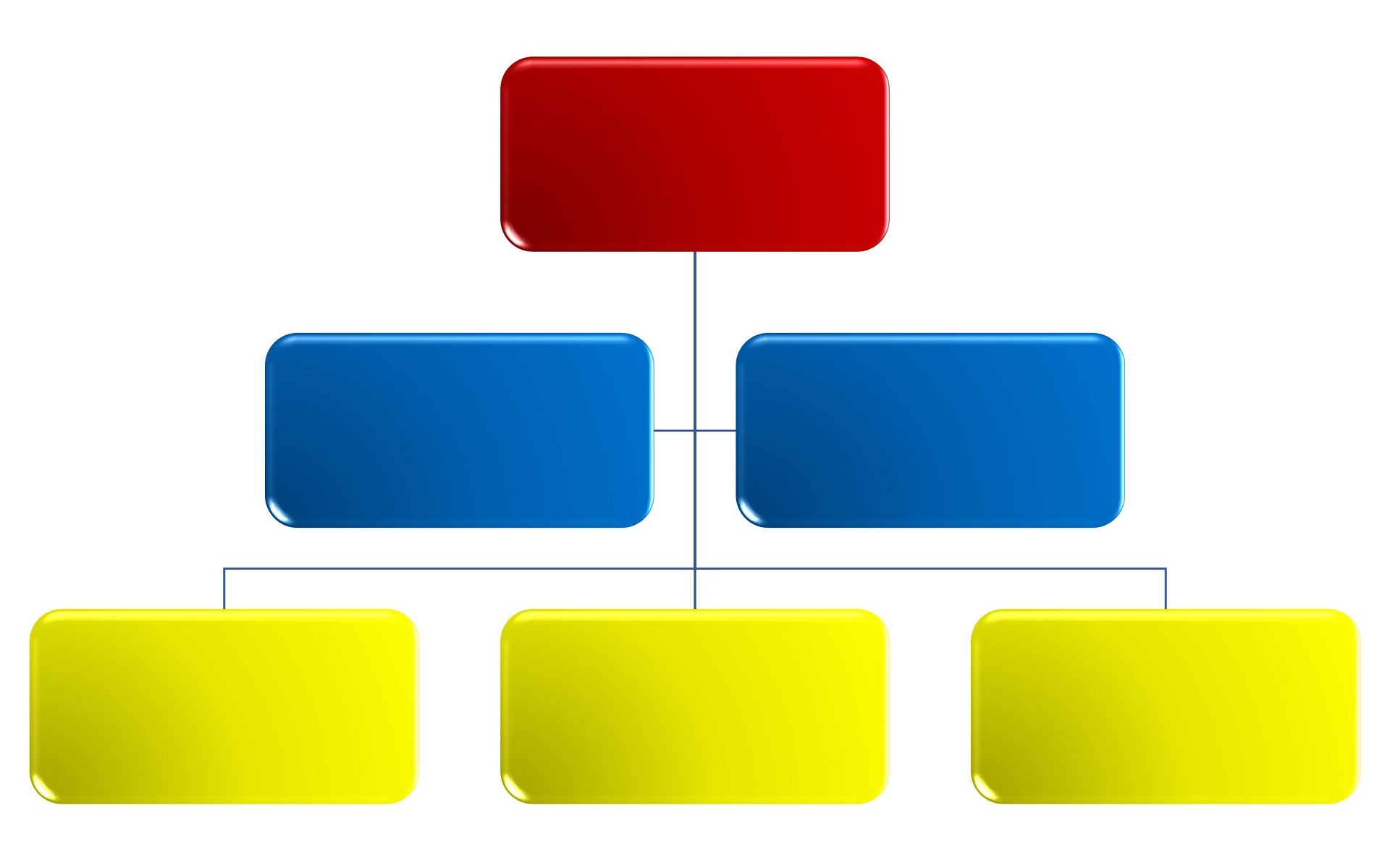

3 Primary Levels/Roles

As you can see, knowing which career path to take means that you need to understand yourself well and articulate where you’d fit into any organization. To do that, it helps to understand that there are essentially main three levels and, therefore, three main career roles you can choose to have within an organization:

- Production – those doing the work/executing the mission to achieve the vision.

- Mid-management – those overseeing teams of producers to ensure the work/mission is getting done.

- Executive management – those setting and adjusting the direction of the organization based on the vision and big-picture data.

At this point, you may be thinking that there can be more roles than these three, and, of course, you’d be right. Just like you can have many nuanced shades of the color red or blend red with the other two primary colors to make other colors, you can do the same with these three primary roles. It’s simply a great starting place in figuring out your workforce identity.

You may have also noticed that these levels were alluded to before when we were looking at career paths. That’s because they match particularly well with the typical career ladder. However, whether you’re on a career ladder or lattice, these three primary roles and levels within an organization still apply.

You’ll want to know more about them so you can know where you fit best, so here’s a little more information on each.

Individual Contributor/Producer

According to Stephen Covey in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, “A producer does whatever is necessary to accomplish results, to get the golden eggs.” Covey gives examples, such as an architect drawing up blueprints. An individual contributor role can be where you start when you’re entering a career, and you can also stay with it your whole career, developing eventually into a senior level producer or subject matter expert (SME). The main pitfall of remaining at this level, of course, is the perception that you should “age out” of the role at a certain point and move into mid-level management or that you won’t find sufficient intellectual challenge remaining in the role. However, some senior level SMEs find their place within an organization serving happily as highly effective individual contributors on a long-term basis, even until retirement. Some leave the organization to become independent freelancers or consultants.

Manager

Again, turning to Covey, we get a helpful definition, “…when a person sets up and works with and through people and systems to produce golden eggs, that person becomes a manager… An architect who heads a team of other architects is a manager.” As you probably already know, this is the where the traditional career path will usually take you. If you’re not there yet, you might be wondering if it’s the role you really want. The role is for you if you truly enjoy hiring and developing talent, as well as delegating and overseeing team activities. Although you can be a manager who also produces, you will need to ultimately care more about the team’s golden eggs as a whole. Most organizations will let you test the waters with project and team lead opportunities first. But the truth is that putting your toes in the water isn’t the same as jumping into the deep end. That’s why some newly promoted managers come to the realization that just because they’re good at leading doesn’t mean they enjoy managing a team full time, whereas others who truly love it may stay in mid-level management until retirement.

Strategic Leader

There are usually two paths to the executive team: founding/co-founding the organization or being promoted from mid-level management. Whether a person is well-suited to a strategic leadership role is strongly tied to aptitude in seeing the whole picture – internally in the organization and externally in the marketplace – and being able to determine the best strategy and direction based on that data. Covey uses an apt metaphor for this role in which he imagines the team in a jungle where the strategic leader “climbs the tallest tree, surveys the entire situation, and yells, ‘Wrong jungle!’”

The interesting thing about this role is that you can develop yourself for it, and, like the other roles, your comfort with it can also be tied to personal preferences. Some workers who show an aptitude for strategic thinking early in their careers might feel frustrated and impatient as they may be forced to climb a long, slow ladder until their aptitude can finally blossom and come to fruition. Another challenge is when strategic leaders feel weary and burnt out from wearing the crown but find themselves trapped. On the other hand, many leaders thrive so much in the role that retiring is unthinkable and ongoing they become mentors, consultants, board advisors, etc.

Further Insights & Recommendations

We’ve looked at the two main career paths, and we’ve outlined the three main levels and roles inside organizations. By now, you’ve probably got a good idea of what you prefer. However, I just have a few more insights to share that will either help you further validate your current choices or help you further clarify your future choices.

Like I mentioned earlier, your choice for which role you have in an organization isn’t necessarily etched in stone. It can be simply where you are on your career path at the moment, and your desire for a role may change as you evolve and grow. Or it can be who you really are as a defining trait in your workforce identity – you may be aspiring to it, or you may want to stay in it once you’ve arrived because the role and you are made for each other.

Speaking of defining traits, what about personality traits? Some believe that your personality reveals what you should do in your career. While I agree that it can definitely help to factor in that information, it’s best not to rely solely on feedback and assessments about personality traits to make career decisions. Case in point: I once worked with an engineer who had chosen engineering because he was good at math and science, and a personality assessment he took in high school indicated he would excel in a career as an engineer. After 14 years in the field, he decided to act on his dissatisfaction with the career he had picked when 18 years old and began to explore other options. Before he met with me, he had taken another personality assessment. With obvious frustration, he said, “It told me I should go into engineering. Please help.”

Personality traits indicate how you will do what you do, not necessarily what you should do. If you follow the logic that personality traits should define career choices, then introverts would never choose to be celebrities or work in the public eye. Yet, many famous introverts have influenced our culture, such as award-winning actress and UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador Audrey Hepburn, British Prime Mister Winston Churchill, and activist Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., to name a few.

For that engineer and others who I’ve supported over the years, personality traits are clearly only one piece of the puzzle. I believe it’s even more important to examine your personal preferences and drivers. You’ll find the clues and the signs that point to that information within your experiences. Without experiences, you can’t uncover the information you need, and this is why it’s so important to try things out. If you think you’d like to move into management, test your theory by taking on more managerial responsibility to see if you’ll like it. Only with experience will you really know whether it’s the right role for you.